There’s a standard set of specifications that appear in boatbuilders’ sales brochures and on yachtbrokers’ websites: LOA, LWL, displacement, sail area, ballast ratio, D/L, SA/D and so on. Most buyers rely on these to some extent, to read between the lines of the marketing literature, but the figures quoted aren’t actually as clear cut as most people think, and some of them are often misconstrued.

How useful are they really and how can you be sure that you’re actually comparing like with like? Let’s take a quick walk through the dimensions, measurements that are widely quoted in yacht specs. There’s a huge amount to consider when buying a sailing yacht and it’s very important to get it right.

Size matters

Let’s look first at the principal dimensions of the yacht. Most sailors are very familiar with them, but many don’t actually know precisely what they mean – and precision is important when you’re comparing small differences between similar boats.

Don’t fall into the trap of assuming that a boat’s model number represents its exact length. A Generic 34 may be 32ft long, for example, and a White Boat 37 could be 39ft. The North Sea 24 (an ancestor of the Rustler 36) is actually 31ft long – 24ft was her waterline length which used to be the minimum required by RORC. Some builders overstate their boats’ lengths in model numbers to make the price tag look like better value, while others understate them because it makes the yacht feel bigger when comparing to other yachts that are perceived to be the same length. Even when the model number does reflect the boat’s actual length, you need to know which length are they referring to.

LOA

It stands for length overall. Surely this is the overall length of the yacht? Quite often it isn’t. Technically, the ‘overall’ only includes the hull from the tip of the stem to the aft edge of the stern. LOA is the overall designed length of the hull and excludes things like overhanging pulpits, bow rollers removable bowsprits and transom-hung rudders. However, some boatbuilders include everything attached to the hull in their LOA figure.

LOA including bowsprit

Many yachts are fitted with permanent bowsprits, either for flying code sails and gennakers or because their plumb bows need a protruding bow roller for anchor clearance. Some builders have started listing ‘LOA including the bowsprit’, which is fair enough as that’s the length you’re most likely to be charged for in harbours, but don’t be misled into thinking you’re buying a bigger boat. At Rustler, we prefer to fit removable bowsprits to give an offwind sail forward clearance from the headsail – and when fully retracted it will save you money in marinas.

Hull length (LOD)

This is the length of the hull without the pulpit, bow roller, bowsprit, rudder stock or any other appendage. Yes, it’s the same as the technically correct definition of LOA, but builders and dealers often use the term ‘hull length’ or its old-fashioned equivalent, length on deck (LOD) to avoid confusion. The savvy sailor quotes this length to any berthing master asking ‘What’s the length of your boat please?’ Knowing this length when looking around boats will help you compare all 37ft yachts or all 42ft yachts equally. These days a yacht with an LOA of 42ft might be a 37ft yacht with a 5ft bowsprit, but she’ll seem much smaller inside when compared to other 42ft yachts.

LWL

This is the length of the yacht at the waterline, measured along the centreline. Anyone who has looked at a boat’s waterline at the end of the season after offloading the sails, cushions, tools, loose gear and the year’s supply of tinned provisions will know that the waterline varies. The figure quoted in yacht specs is usually the DWL (design waterline) but to muddy the water it may be the half load or full load waterline length – the length of the waterline when the yacht is carrying half or all of the maximum load she was designed for. Half load is the most realistic figure for general cruising purposes.

Waterline length is a key factor in determining a yacht’s hull speed, which is effectively her maximum speed through the water (unless she can aquaplane, and cruising yachts generally can’t do that). Hull speed in knots is roughly equal to 1.34 times the square root of LWL in feet. A long waterline length is therefore assumed to be better than a shorter one.

However, it’s worth knowing that many sailing yachts with a traditional shape (including some Rustlers) are designed so that their actual waterline length increases significantly when they heel over, which means they are a fair bit faster upwind and on a beam reach than their static waterline length would suggest. And it’s also worth bearing in mind that in light winds the fastest hull with the least drag is not necessarily the one with the longest waterline.

Beam

Unlike length, beam is straightforward – the figure quoted in the specs is simply the width of the boat at its widest part. Some modern cruising yachts have extremely wide beam, which increases the internal volume of the hull and allows for wider beds in the aft cabins, but has its drawbacks. Wide beam can add a useful amount of form stability to the righting moment of the yacht, which is more comfortable for the crew. If the wide beam is carried all the way aft in the hull, the yacht will benefit from twin rudders. But these don’t give the helm as much manoeuvrability in harbours as a single rudder due to lack of prop wash over them. And if you want to cruise in places like the Netherlands and Baltic, where most berths are in ‘boxes’ between fixed posts, wide beam can make it a lot harder to find a place to moor for the night and make berthing fees more expensive.

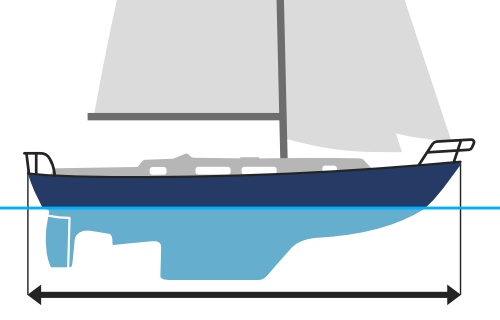

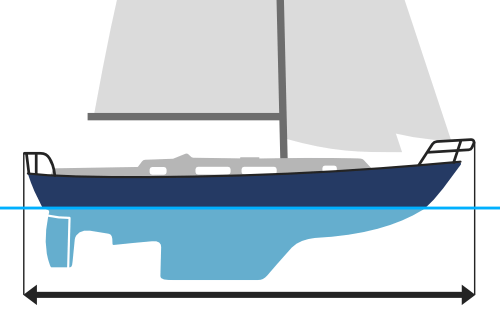

Draught

In the UK we call it draught, in the US it’s draft. Either way, it’s measured from the waterline down to the tip (bottom) of the keel – it’s the depth of water the boat needs to float. Like waterline length, draught is variable, depending on the load the boat is carrying and also on the salinity of the water. Boats are less buoyant in fresh water than in seawater (and brackish water is somewhere in between). In practice, a sailing yacht’s draught can increase by 5-10cm (2-4in) when moving from salt water to fresh, and it can increase by a similar amount again when a boat is fully loaded, something to bear in mind if you intend to take a fully-loaded yacht through the French canal system.

Often, your draught will be dictated by your chosen cruising ground. In areas like the Bahamas and the east coasts of the UK and US, shallower draught can be a distinct advantage.

The difference between displacement and ballast

It may seem obvious but many boat owners confuse displacement with ballast, assuming that heavier displacement means a yacht is more stable and therefore safer and more seaworthy. That’s often not true at all.

Ballast

Ballast is weight that makes a positive contribution to the yacht’s stability. The location of the ballast is just as important as its weight – the lower (or deeper) the better. In most cases a yacht’s ballast is simply the weight of its keel but there are some exceptions. Some long keel, lifting keel, swing keel and centreboard yachts have internal ballast, some racing yachts use water ballast, and in any yacht with a deep bilge, heavy equipment installed below the waterline effectively acts as extra ballast. That said, when comparing monohull yachts you won’t go far wrong by assuming that the ballast is just the weight of the keel.

A shallow keel needs more ballast weight to achieve the same righting moment as a deep keel. Some builders who offer shoal draught and deep keel versions of their yachts put the same amount of ballast in both, which means that the version with the shallower keel will be more tender. Others make the shallow keel option significantly heavier, which gives it the same stability as the deep keel version but reduces its payload, or load-carrying ability. It’s important to check this before comparing with other boats. Ballast material is also important. Lead is more dense than cast iron, therefore the keel will be slimmer and/or in a lower position, so there is less bulk below the waterline, less drag and it will give greater stability. All Rustlers have lead keels (either as a fin, encapsulated or as a stub keel).

Learn more about Rustler keels

Displacement

This is the yacht’s total, all-inclusive weight (more precisely, it’s the mass of water displaced by the hull as it floats, but in practice that’s essentially the same thing).

When comparing boats, it’s important to know what displacement figure is being quoted in the specs. It’s most likely to be light ship displacement (the weight of the yacht with her standard equipment, fixtures and fittings, but nothing else). However, it could be the half-load displacement (sometimes called the sailing load), which is usually about 10 per cent more than the light ship displacement and normally includes the weight of a typical crew and their kit, half-full tanks of water and fuel, a significant weight of provisions and so on. It could also be the full load displacement, but that’s less likely to be quoted in the specs.

If you’re looking at boats, it’s well worth asking the builder or dealer for all three displacement figures: light ship, half load and full load. Then you’ll be able to make direct comparisons with other boats, you’ll know the boat’s actual displacement in typical cruising use, and you’ll be able to work out her payload, which is important if you’re going to be loading her up for long-distance cruising. Some yachts’ sailing performance and handling are quite similar at all three load states, for others the load state can make a real difference.

When comparing displacement figures and using them to work out ratios, make sure you’re using the same load state for all boats. Otherwise the results could be misleading. At Rustler Yachts we list the light ship displacement but assess stability in both light ship and sailing load to give a fairer representation of the yacht’s traits.

Sail Area

Some boatbuilders, like Rustler, give the area of each individual sail in their specs. Others give the total area of the yacht’s working sails as a single figure. For a sloop, this is the area of the full mainsail and the standard headsail, whether that’s a genoa or jib. For a cutter (like the Rustler 42, 44 and 57), it’s the area of the yankee, staysail and mainsail combined. For a boat with a slutter or solent rig, where only one of the two headsails is used on most points of sail, it’s worth checking which of the headsails – genoa or staysail – is the working sail.

Learn more about why we choose cutter rigs for our offshore cruisers

The sizes of offwind sails – spinnaker, gennaker, cruising chute or code zero – are usually given separately. There’s often more scope for customising the cut and size of these sails to suit your preference and your style of sailing.

Now you’re armed with the knowledge of what these figures mean, what can you do with them? They can be used in formulas to help discover more about the characteristics of a yacht. Sometimes a light-displacement boat can weigh more than a heavy-displacement yacht. Confused? Hopefully you won’t be after reading about the most commonly used ratios.